Government workers feel inflation’s pinch as wages lag

Public-Private Wage Gap

In a red-hot labor market, workers across the United States are negotiating and receiving wage increases at the fastest pace in decades. But a crucial part of the workforce that has been keeping the country running during the pandemic is being left in the dust.

Government workers — teachers, firefighters, sanitation workers, bus drivers, city government employees — who make up more than 15 percent of the U.S. workforce, have seen their wages lag significantly behind those employed by private industry over the past year.

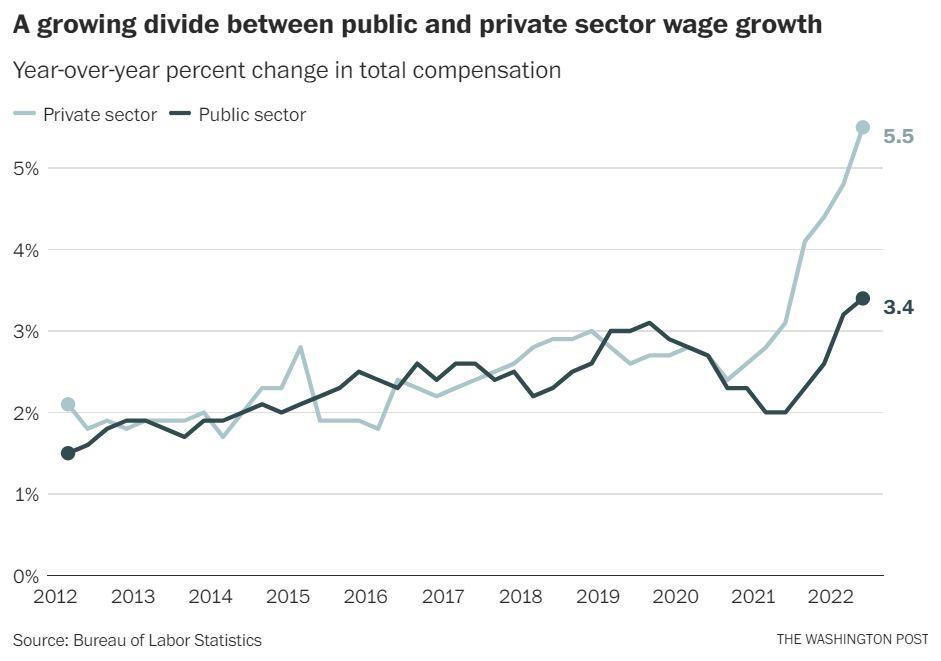

Wages in the private sector rose by 5.5 percent over the past year, the highest increase in the history of the data, but wage gains for state and local government workers have trailed behind, rising by 3.4 percent, according to data from the Labor Department’s employment cost index released on Friday.

While wages across the board have not kept up with soaring inflation, now at a 40-year high, the sting of rising prices has fallen disproportionately on the workers who take trash to the landfills, keep city governments running, fight wildfires, and transport Americans to and from work and school.

Many of these workers who chose jobs in the public sector because of robust benefits and out of a commitment to public service are facing tough choices as housing, gas and food prices have skyrocketed over the past year.

“It’s really striking how much wages are trailing for public-sector workers,” Guy Berger, the principal economist at LinkedIn, said. “The sector is not doing great. When you talk about sectors that are booming right now, it’s not just one of those.”

Crystal Bolster, 43, is a legal secretary for the public defender’s office in Spokane, Wash. After two decades working for the county, she makes $39,000 a year. She said the price of basic needs has increased so much this year that she has become further resigned to the idea that she may never be able to afford her own place. She lives with a roommate and her three sons in a two-bedroom rental.

“It’s been difficult for a while, but this year is worse,” she said. “We’re making tough choices on what we buy for groceries and whether we’re going to drive anywhere because of the gas prices. We don’t buy beef anymore. We don’t buy Cap’n Crunch. We don’t indulge in cold brew coffees.”

This year, Spokane County managers are offering county workers, who are represented by AFSCME Local Union 1553, a 3 percent pay increase, followed by two years of 2 percent annual raises.

“A lot of people are angry because we’re so far behind inflation,” Bolster said. “These raises won’t make that much of a difference for most of us. A 3 percent raise is $96 more a month for me. That won’t even cover my power bill.”

The widening gap in wages between the public and private sectors has produced a cascade of problems for public-sector workers. It has exacerbated an understaffing crisis in government jobs, with public-sector workers quitting in droves to take higher-paying jobs in private industry, and has increased workloads for those who remain. In many parts of the country, there is a severe shortage of bus drivers, government workers and teachers.

While the private sector had more than recovered all of its pandemic job losses as of June, only 57 percent of the government jobs lost during the pandemic have been refilled, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data.

“It’s a huge problem,” said Heidi Shierholz, president of the Economic Policy Institute, a left-leaning think tank. “Inadequate pay has been a huge reason teachers and support staff in state and local government have quit. In order to attract and retain workers they need, they will have to not just hire workers but raise pay.”

Government jobs have never paid as well as those in private industry. But they have attracted workers with the promise of pensions and strong health-care benefits, job security and an opportunity to serve the public. As these benefits have been eroded over the years, more workers are having more trouble justifying working in the public sector.

Interviews with a dozen public-sector workers and union officials from around the country, including public school teachers, parole officers and administrative staff, suggest that the workers who perform the labor that runs the country face increasing financial duress at home while their workloads climb higher as job vacancies remain unfilled.

Sean Small, the president of the IFPTE Council 21, which represents close to 1,000 municipal workers in Newark, said that city government workers had their wages frozen between 2003 and 2016, and have only received a $4,600 pay increase since then.

“My average member makes $45,000,” Small said. “Members can’t afford to buy gas. They can’t afford to buy groceries. They are getting extra jobs and unfortunately some have to borrow from other members or their pension to make ends meet.”

Even as inflation and rents soar in Newark amid spillover gentrification from New York City, Small said the city is currently offering a 2 percent raise in contract negotiations.

Andee Sunderland went on an eight-day strike in April with thousands of Sacramento teachers over heavy workloads, wages that weren’t keeping up with inflation, and the prospect of 400 teacher vacancies in the coming year.

Sunderland made $225 a day as a substitute teacher, and ultimately won a 25 percent pay increase with back pay following the strike, but the city has still not come forward with her back pay.

“By the end of the school year, it was hard to afford gas to get to work,” Sunderland said. “I’m behind on my car payments. That’s true because other costs have gotten so out of control. I just can’t even imagine going on vacation.”

The Sacramento Unified School District said Sacramento teachers are scheduled to get back pay by Aug. 3.

“Sac City Unified substitute teachers receive some of the highest pay in the greater Sacramento region,” said Brian Heap, a spokesman for the school system. “It had been our goal to deliver [back pay] sooner, however there were some challenges in gathering all the necessary information for processing the payments.”

Most public-sector workers do not have the ability to negotiate over their individual wages and salaries after they have been hired into a role, sometimes because of legal barriers. In unionized jobs, wage increases are typically negotiated by the union and determined by the government. For public-sector workers who aren’t unionized, securing wage increases is often at the mercy of elected legislatures. Thirty-four percent of government employees in the United States are in unions.

Conservative policymakers blamed public-sector unions for making wages lag behind the private sector, saying they lock workers into contracts that cannot easily adapt to shifting economic conditions.

“Our basic principle is you should be compensated based on the value you create in any occupation, public or private sector. Union contracts prevent that from being the case,” said Akash Chougule, vice president of Americans for Prosperity, a right-wing advocacy group tied to the network run by the billionaire Koch brothers. “Sometimes poor performing employees are overpaid and overperforming employees are underpaid. This makes it impossible to reward high-performing employees.”

AFSCME, the country’s largest public-sector union, representing 1.3 million workers, said wages and conditions in non-unionized public-sector jobs are worse than they are in unionized positions because workers don’t have the ability to collectively bargain, leaving wages and benefits up to elected officials who are often concerned with keeping expenditures low.

Andrew Bernier, a civil engineering technician with the U.S. Army’s Cold Regions Research and Engineering Lab in Hanover, N.H., said he has had to cut back on a lot of basic expenses because of inflation, even with a salary of $82,000 a year for a family of four.

“I don’t make that bad of a salary, but it doesn’t go very far,” he said.

In recent years, his family opened its own day care to save on child-care costs, which used to run $2,000 a month per child. But even with the day-care income, they feel squeezed. The family has stopped shopping for meat at the grocery store.

“Once we receive our tax return, we get a whole cow, chickens and usually one or two pigs,” Bernier said, noting that a farm raises the livestock and later sends it to a butcher to cut and package, which Bernier then preserves in a chest freezer at home. “It’s $1,500 for a cow but you’re paying only $4 a pound.”

Meanwhile, his colleagues are quitting the Army lab en masse to work in the private sector.

“The [lab] is hiring as fast as they can, but quite a few candidates have turned down positions due to pay,” said Bernier, who helps engineers build equipment for research. “In the private sector I could make a lot more, but I like my job so I haven’t considered leaving.”

A number of state governments, including in Connecticut, Florida, Missouri, Idaho and South Dakota, are running record surpluses and can afford to pay their workers more, but are hesitant to loosen their purse strings for permanent raises, union leaders say.

Vacancies throughout the public sector mean that more of the workers who remain have been pushed to take on extra job duties without extra pay, potentially delaying important tasks. Worsening conditions produce a feedback cycle where more workers quit their jobs as vacancies mount.

“When there’s significant understaffing, that means important work doesn’t get done,” said Lee Saunders, the president of AFSCME, via email. “It leads to excessive overtime which leads to burnout, further exacerbating staffing issues,” he said, noting that ongoing shortages in patient care facilities, psychiatric hospitals, corrections facilities and schools are creating unsafe conditions for workers picking up the extra load.

Rayneika Robinson, a parole officer for the Maryland Department of Public Safety and the vice president of AFSCME Local 3661, which represents all parole and probation agents in Maryland, said that many of her members are leaving, even though they just received an 11.8 percent raise spread out over two years. The current starting salary for a parole officer in Maryland is $49,496.

“Members are extremely grateful for the salary bumps, but we started so far behind that we continue to struggle,” said Robinson, who works in Elkton, Md. “We have a very stressful job and it’s important to do little things for myself like get my nails done, but I had to cut that out. I’ve heard people who’ve had to cut back on different family activities because they can’t afford the price to get into an amusement park.”

As officers have quit for higher-paying jobs in other states and private industry, Robinson has found her caseload increase to 280, along with an expectation that she take on new administrative responsibilities.

“It’s very overwhelming because theoretically how is it possible to touch every file every month while juggling playing secretary, intake and monitoring cases? We’re not seeing administrative, clerical and intake positions filled. You can go to other states and make more doing the same thing, or go federal. Just to be honest, I’m looking for other opportunities.”

Lauren Kaori Gurley, Washington Post - August 1, 2022 at 11:15 a.m.